Introduction to Risk Assessment for Decision-makers

Applying science-based climate change services at a sectoral level in the Pacific is typically undertaken to estimate the type and level of climate change risk that needs to be managed or otherwise mitigated. In turn, this risk is often estimated through evidence-based, sector-specific climate change hazard identification, vulnerability and impact assessment.

For such assessments, it is important for decision makers to focus on the most important information needs and not get overwhelmed by technical detail. It is also important to systematically address the issues in order from high to low priority.

The nature of climate change risk

Risk is generally defined as a combination of the likelihood of an occurrence and the consequence (either positive or negative or both) of that occurrence. Often, the exact likelihood and consequences are not known, but risk management activities are put in place to reduce or mitigate the risk.

By way of example, studies show that young drivers have a high risk of being injured in a car crash. In practice, however, neither the likelihood nor consequences of this occurring are known with certainty – we cannot be sure which individuals will be injured, or the total number and nature of the injuries. Still, this risk is actively mitigated by safety campaigns encouraging young drivers to slow down when driving.

Similarly, there are uncertainties associated with climate change risk. Although we can be confident that the climate is changing, we do not know exactly how much greenhouse gas society will emit into the future, nor do we know the magnitude of the related changes in climate variables in some regions. The exact tipping point or threshold at which climate change could impact our area of interest is also unknown, as is how people will respond to future circumstances (measure of adaptive capacity) and what the effectiveness of these responses will be (measure of resilience).

Nonetheless, we may be able to estimate the consequences of particular events even though we are uncertain as to their likelihood, and thereby potentially mitigate impacts. For example, we know well the devastating consequences of prolonged drought on the livelihoods of farmers. Hence the consequences of an increase in drought frequency and intensity due to climate change can be estimated with confidence, even if the probability of such an event is itself very uncertain. Risk management responses can then be better tailored for specific circumstances, locations and communities of interest; thereby mitigating impacts in a more effective and efficient way to achieve preferred outcomes.

Assessing climate change risk

Approaches

There are several ways to approach climate change risk assessments:

- Impact assessment is used if the focus is on determining the effects of climate change on the subject of interest, typically at a sectoral level (e.g. impact of projected climate on land suitability for cultivating bananas)

- Vulnerability assessment is used if the analysis considers both the expected impacts and the capacity to prevent or adapt to these impacts (e.g. vulnerability of farmer community by considering impact of climate change on banana cultivation and the capacity of banana farmers to adapt)

- Risk assessment is used if the focus is on minimising the likelihood of consequences through a risk management perspective (e.g. risk of changes in area suitable for banana plantation caused by projected increase in air temperature).

These are all complementary assessments, and risk assessment is sometimes used interchangeably as a generic term for them all.

This document introduces the overall steps usually taken in climate change risk assessment and management incorporating science-based climate change information as evidence to inform decision-making. It is intended to provide an overview of the risk assessment process only, as context for developing climate change information to inform such a process, and stakeholders are advised to refer to more detailed guidance as appropriate for undertaking structured, multi-hazard, sector-based climate change risk assessments.

Factors to consider

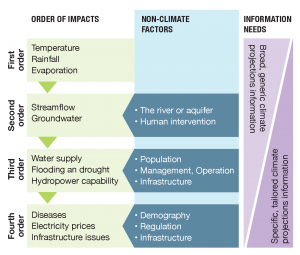

The risks or impacts of climate change to a sector in a region do not only appear directly from changes in global, regional and local climate variables but from a chain of impacts (see Fig. 1). The changes in global climate cause changes in regional/local climate (first order impacts), which in turn may change the streamflow and groundwater of a region, depending on the characteristics of the river or aquifer and human activities such as land use (second order impacts), and so on. The higher the order of impact, the more factors (not just climate) influence the subject of interest.

Climate projections are necessary to assess first order impacts, such as changes to climate variables including temperature and rainfall. The type of climate projection information required could differ from one assessment to another. For example, the level of detail or complexity often increases with the order of assessment. As higher order impacts are assessed, non-climate factors must also be taken into account.

Depth of assessment

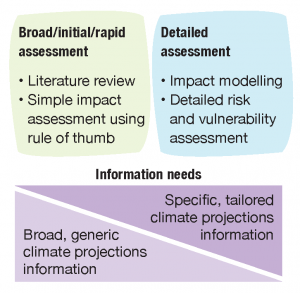

Risk assessments can be conducted to varying depths – from preliminary rapid assessments through to detailed quantitative risk assessments, depending on the situation. Not all problems need a detailed assessment to provide an answer. A rapid assessment is sometimes all that is necessary. If more information is required, the rapid assessment can be built on in stages to result in a more detailed assessment.

Rapid assessments

A rapid assessment, which may also be referred to as a broad, initial or preliminary assessment, is a useful way to conduct risk screening. It allows for quick identification of risks with relatively small resource and effort input. A rapid assessment is a suitable tool for decision-makers and planners to use when they are not sure how, or if, their decision or plan could be affected by climate change.

A rapid assessment uses existing climate change information, such as the information available at www.pacificclimatechangescience.org, to conduct an assessment that identifies and appraises key hazards, vulnerabilities and associated risks as early as possible. If necessary, the outputs of a rapid assessment can serve as the basis for a more detailed examination of risks, or to determine the most effective solutions. A desktop study, a workshop and/or focus group discussion are all ways this might be carried out.

Qualitative and generic quantitative (semi-detailed) assessments

Qualitative and generic quantitative risk assessments are useful when more detail is needed than in a rapid assessment, but a full, detailed assessment is unnecessary. They can be undertaken using a range of qualitative to simple/semi-quantitative techniques where suitable climate change data are readily available (e.g. www.pacificclimatechangescience.org) or easily developed (see Developing Climate Change Information steps 5 and 6).

For example, if the literature shows that rainfall elasticity of streamflow in a particular region is 1.5 (meaning that a 10% change in mean annual rainfall results in a 15% change in mean annual streamflow), then based on such a ‘rule of thumb’ and the available annual rainfall projection information for the region, the potential change in annual streamflow due to projected change in rainfall could be estimated. This semi-detailed approach was used in the sweet potato farming case study.

Detailed assessments

A comprehensive, more detailed quantitative risk assessment can be complex. It usually requires more specific, tailored, climate change data (which may not be readily available), and/or additional expert technical advice to collate, prepare and interpret the data. This type of assessment may be used to address uncertainties in the likelihood of projected changes (i.e. understanding the climate change itself); further analyse the sensitivity of particular risks to changes in certain climate variables and non-climate variables; or assess various adaptation options.

A detailed assessment can be undertaken using quantitative, multi-disciplinary science techniques (i.e. in addition to climate projections) including application of various coupled mathematical models, such as for (hydrological) water balance, crop simulation and bio-economics. In this context, climate change information usually has to be tailored for the particular impact model(s) used.

IMPORTANT: A useful way to think of a stage-based risk assessment is as a medical check-up at a doctor’s surgery. A rapid assessment is like a visit to the General Practitioner (GP), while a detailed assessment is like a follow-up visit to a medical specialist if the GP has identified a potentially more serious health problem. Most times, it is only necessary to visit the GP to find the information we need to solve any health issues (and the GP is much cheaper and quicker than a specialist).